Gold, Green, Diamond: What You Should Know About Open Access Publishing Models

- Authors

- Topics

The Open Access (OA) movement is quite complex: it involves diverse principles, models, and policy frameworks. The goal of this tutorial is to introduce learners to the origins and evolution of Open Access and provide insights into its objectives and global impact.

Learning outcomes

Upon completing this tutorial, learners will be able to:

- understand the historical development of the Open Access movement, including key milestones and pioneers;

- differentiate between different Open Access models and comprehend their associated terminology and concepts;

- scrutinise international Open Access policies and strategies, and assess their implications for both readers and authors; and

- apply best practices for Open Access publishing to their research and institutional environments.

Consolidation of the publishing industry

Between the 1950s and 1980s, the landscape of scientific publishing underwent a profound transformation as large commercial publishers rose to global dominance. During this time, smaller society presses — often run by academic communities or professional organisations — increasingly struggled to keep up with the growing volume of research and the increasing complexity of publication demands. Unable to manage the scale of operations effectively, many were either overshadowed or absorbed by corporate publishing giants such as Elsevier, Wiley, Springer, Taylor & Francis, and Sage. These companies streamlined operations for editing, production and distribution, capitalising on economies of scale to establish a dominant position in the market. To this day, large publishers control 40% of the global scientific publishing market. Elsevier alone accounts for 16%.1

The accumulation of power in the publishing industry turned the dissemination of research into a highly lucrative business: Elsevier, for instance, reports an annual profit of 1.2 billion Euros. With a profit margin of 37.8%,2 Elsevier outperforms by far the likes of technology giants Alphabet and Apple.

By consolidating journals under their banners and leveraging exclusive contracts with libraries and institutions, these corporations created a system in which access to scientific knowledge became increasingly cost-prohibitive. The subscription fees for academic journals skyrocketed, placing immense financial strain on libraries, universities, and research institutions.

Smaller institutions, especially in developing countries, found themselves unable to afford access to critical publications. This inequity created barriers for researchers and widened the gap between well-funded institutions and those with limited resources. The restrictive nature of the commercial model hinders the broad dissemination of knowledge, which, in turn, limits the reach and impact of scientific research across the globe.

A growing dissatisfaction with commercial publishing models and the barriers they imposed on knowledge sharing set the stage for the emergence of the Open Access movement in the late 20th century. Advocates of Open Access envision a world in which anyone, regardless of their financial or institutional support, can access and benefit from the latest research.

The foundations of Open Access

The 1990s marked the beginning of a new era, driven by the transformative potential of the internet and the digital revolution. For the first time in history, it became possible to share research globally and instantaneously. Publishing on the internet is significantly cheaper than traditional methods, as it eliminates the need for physical printing, binding, and shipping of journals or monographs. This reduction in production and distribution costs allows research to reach broader audiences with unprecedented efficiency, paving the way for a more accessible and interconnected landscape of scholarly communication.

This era also saw the emergence of tools like like Open Journal Systems (OJS), which researchers can use to create and manage their own OA journals without the mediating role of commercial publishers. Non-commercial OA journals began to flourish, as digital technologies enabled the creation of new journals while also facilitating the digital conversion of existing print journals. The Directory of Access Journal (DOAJ) recorded significant growth, with the number of online journals that are free of charge to both readers and authors increasing from 100 to 800 in just a few years. This period marked the birth of a global Open Access movement that challenged traditional publishing norms.

Gold vs. Green Open Access

The early 2000s saw the formalisation of Open Access principles and models. Two pioneers, Stephen Harnad and Peter Suber, played pivotal roles in defining the movement.

Harnad, a Canadian cognitive scientist based in Montreal and founder of the CogPrints repository (1997), introduced the first Open Access Journals.

The gold route refers to articles made freely available to readers by publishers immediately upon publication. This model relies on funding mechanisms, such as Article Processing Charges (APCs), to cover publishing costs. An APC is a fee paid by authors or their institutions to cover the costs of publishing an article in an Open Access journal.

The green route, on the other hand, provides a complementary approach to Open Access. In this model, authors retain the right to archive a version of their work — either the preprint (before peer review) or postprint (final, peer-reviewed manuscript) — in open-access repositories in addition to being published in a scholarly journal. These repositories may be institutional (see for instance RUN-Repositorio da Universidade da Nova), discipline-specific (for instance RePEc, which focuses on Economics), or general-purpose platforms (such as HAL or Zenodo): they ensure the work is freely accessible to the public without requiring additional fees.

Peter Suber, a philosopher specialising in the philosophy of law and open access to knowledge, emphasised the importance of treating knowledge as a public good.3 As director of the Harvard Office for Scholarly Communication and director of the Harvard Open Access Project (HOAP), he championed diverse funding mechanisms for OA, arguing that the movement must transcend commercial interests to remain inclusive and equitable.

What’s wrong with APCs?

The emergence of Article Processing Charges (APCs) as a funding model in the Gold Open Access route introduced significant challenges. In the APC model, costs associated with publishing — such as editing, peer review management, and digital dissemination — are transferred from readers to authors or their institutions. While this model removes barriers for readers, it creates new ones for researchers, particularly those from underfunded institutions, low-income countries, or independent scholars without institutional support. This shift effectively perpetuates inequities in the academic publishing system, as those unable to pay the charges are excluded from contributing to the global pool of knowledge.

Moreover, the APC model allows commercial publishers to maintain their position as the gate keepers of knowledge. While access to readers may improve with the APC-funded gold route, the underlying power dynamics and financial structures remain largely unchanged. When all is said and done, the APC model highlights the limitations of relying on market-driven solutions to solve systemic problems in academic publishing.

The Diamond Model

In 2012, Marie Farge, a French mathematician and physicist, introduced the concept of Diamond Open Access.4 Unlike the “gold” model, which relies on Article Processing Charges, the “diamond” model was conceptualised to be entirely free of charge for both authors and readers.

Fuchs and Sandoval published one of the first systematic definition of Diamond Open Access (2013):

In the Diamond Open Access Model, not-for-profit, non-commercial organisations, associations or networks publish material that is made available online in digital format, is free of charge for readers and authors and does not allow commercial and for-profit re-use. 5

The introduction of the Diamond Open Access model represents a significant step forward in addressing the limitations of previous Open Access frameworks. By removing financial barriers for both authors and readers, the Diamond Model prioritises equity and inclusivity in scholarly publishing. The emphasis on not-for-profit, community-driven initiatives positions it as a model designed to democratise access to knowledge while safeguarding it from commercial exploitation.

Diamond Open Access quickly gained traction, particularly in regions like Latin America, where 95% of open access journals registered in the DOAJ follow the Diamond Model. Platforms such as Redalyc and SciELO offer robust publishing ecosystems supported by academic and public institutions. Unlike the profit-driven systems dominant in Western countries, Latin American publishers embraced an ethos of “sharing” rather than commercialisation.

As Arianna Becerril-García, director of Redalyc, stated:

The Latin American region, as a result, owns an ecosystem characterised by the fact that “publishing” is conceived as acts of “making public”, of “sharing”, rather than the activity of a profit-driven publishing industry (…) Latin American academic journals are led, owned, and financed by academic institutions. 6

Despite its immense potential, the Diamond Open Access model, faces significant challenges. One of the most pressing issues is the lack of robust preservation mechanisms for many Diamond OA journals. This vulnerability has been described as a “tragedy of the commons,” where the absence of coordinated preservation policies puts valuable scholarly content at risk of being lost.

Addressing this challenge has become a priority for collaborative initiatives like Project JASPER, which brings together non-profit organisations such as the DOAJ, CLOCKSS, and the Internet Archive. These efforts aim to create a sustainable framework for safeguarding OA content, ensuring its longevity and accessibility for future generations.

On the global stage, the importance of community-driven publishing has been increasingly recognised. In 2021, UNESCO’s recommendations for Open Science highlighted the need to treat Open Access as a public good. This aligns closely with the findings of the “Diamond study” commissioned by cOAlition S in 2020 and published in 2021. The study provided a comprehensive overview of the Diamond OA landscape, and identified key goals such as fostering collaborative practices, bibliodiversity, and multilingualism. These goals are seen as essential for creating a more inclusive and representative global scholarly ecosystem.

The Diamond Study estimated that there were over 29.000 Diamond OA journals in 2021, which accounted for 73% of all OA journals listed in the DOAJ. Despite their significant overall numbers, these journals often operate as small-scale initiatives, serving highly specialised or local communities. This “archipelago” of journals showcases the scientific and cultural richness of the Diamond Model but also underscores its reliance on a fragile economy supported by volunteers, universities and research centers. While Diamond OA journals are making progress toward full compliance with international standards like Plan S, they continue to face operational challenges that threaten their scalability and sustainability.

The study’s conclusion calls for the realisation of an Open Access Commons, a vision of a diverse, thriving, and interconnected Diamond OA ecosystem. This ecosystem would champion bibliodiversity, serve multiple languages and cultures, and operate across a wide array of disciplines. Achieving this vision requires not only greater international collaboration but also increased investment in infrastructure and policy support to strengthen the foundations of community-driven scholarly publishing. In doing so, the Diamond model could fully realise its potential as a cornerstone of equitable and inclusive Open Access.

Identifying Open Access routes

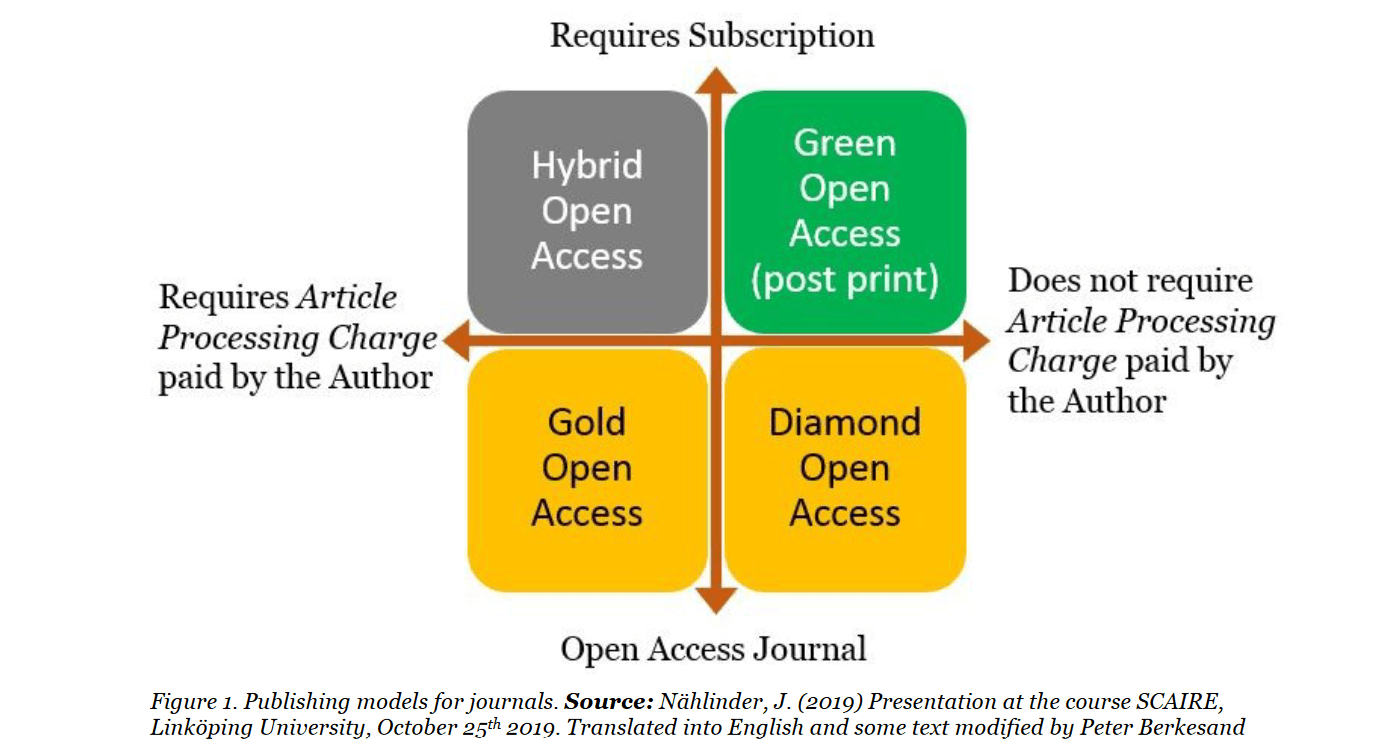

Open Access publishing can be broadly categorized into four distinct models, as illustrated in the diagram below:

The diagram gives you an overview of the four publishing models of Open Access. Source: Nählinder, J. (2019) Presentation at the course SCAIRE, Linköping University, October 25 th 2019. Translated into English and some text modified by Peter Berkesand

These models are defined in terms of their economic structures and their legal frameworks. On the economic axis, journals are either require subscription fees or operate free of charge. The distinction is based on who bears the cost — readers or authors (or their institutions).

A hybrid journal adopts a mixed approach, where the journal is subscription-based but offers authors the option to make individual articles Open Access for an additional fee. This approach has been criticised as a “double-dipping” model, where institutions pay twice: first for the subscription and then for the Open Access fees, exacerbating financial burdens on academic budgets.

Beyond the economic aspect, the legal aspect is a critical factor distinguishing these models. It determines whether authors retain their copyright or are required to transfer it to publishers. Retaining authors’ rights is a cornerstone of true Open Access, as it ensures that researchers maintain control over the dissemination and reuse of their work.

By understanding these routes, researchers, institutions, and policymakers can make informed decisions about adopting and supporting the models that align with their goals for equitable and sustainable knowledge sharing.

DARIAH and Open Access

The Digital Research Infrastructure for the Arts and Humanities (DARIAH) has played an active role in shaping Open Access policies, particularly in the Social Sciences and Humanities (SSH). Recognising the unique needs of these disciplines, DARIAH has long advocated for Green Open Access and APC-free Gold Open Access as more equitable options. See Towards a Plan(HS)S: DARIAH’s position on PlanS.

DARIAH has also emphasised the importance of investing in small-scale publishing services and developing new OA venues to support diverse research topics (see, for instance: Episciences). DARIAH’s vision aligns with the broader goals of the OA movement: to create a publishing landscape that is inclusive, sustainable, and adaptable to the needs of all researchers.

More recently, DARIAH launched its own Diamond Open Access Journal: Transformations. At the time of writing this tutorial, the journal had published its first call for submissions, inviting contributions that engage with innovative research practices, interdisciplinary approaches, and the intersection of technology and the humanities.

Conclusion

The history of Open Access is a testament to the power of collective action and innovation in reshaping global knowledge systems. The emergence of community-driven models as an alternative to the dominance of commercial publishers has transformed the landscape of academic publishing. Understanding the historical context of Open Access, its key models, and international strategies is essential for anyone seeking to contribute to its future.

As researchers, institutions, and policymakers continue to navigate this landscape, the principles of Open Access — equity, inclusivity, and collaboration — will remain at the heart of the movement. By embracing these values, we can work towards a world where knowledge is truly accessible to all.

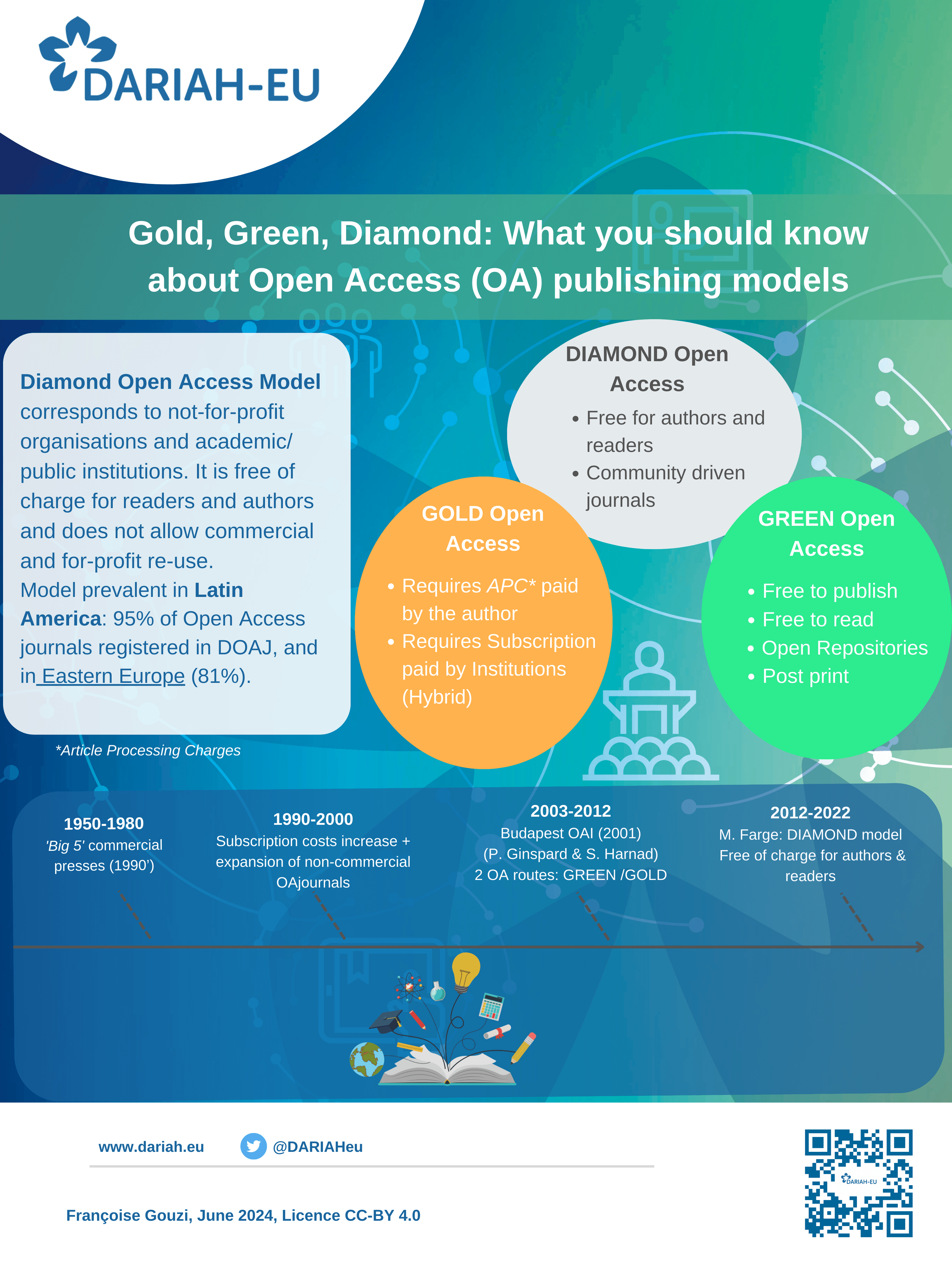

Short visualisation of Open Access routes (with definition of Diamond publishing model and timeline of Open Access movement)

Footnotes

-

Martin Hagve. 2020. The money behind academic publishing. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen, vol. 140. DOI: 10.4045/tidsskr.20.0118 ↩

-

RELX. 2024. Annual Report 2023. https://www.relx.com/~/media/Files/R/RELX-Group/documents/reports/annual-reports/relx-2023-annual-report.pdf ↩

-

Peter Suber. 2012. Open Access. Camebridge: MIT Press. ISBN: 978-0-262-51763-8. ↩

-

Zoé Ancion, Jean-François Lutz, Pierre Mounier and Irini Paltani-Sargologos. 2023. Le modèle d’accès ouvert Diamant: Politiques et stratégies des acteurs français. The Diamond Papers. DOI: 10.58079/12710 ↩

-

Christian Fuchs and Marisol Sandoval. 2013. “The diamond model of open access publishing: Why policy makers, scholars, universities, libraries, labour unions and the publishing world need to take non-commercial, non-profit open access serious”. TripleC. 13 (2): 428–443. DOI: 10.31269/triplec.v11i2.502 ↩

-

Arianna Becerril-García and Eduardo Aguado-López. 2019. The End of a Centralized Open Access Project and the Beginning of a Community-Based Sustainable Infrastructure for Latin America. In Leslie Chan and Pierre Mounier, eds. Connecting the Knowledge Commons — From Projects to Sustainable Infrastructure. OpenEdition Press. DOI: 10.4000/books.oep.9003. ↩